and broaden your impact

The difficult part is to reveal them.»

Galileo Galilei

each one’s humanity

Delfi's Oracle (as reported by Socrates V century B.C.)

to increase results

Mies Van Der Rohe

to navigate complexity

Albert Einstein

Anna Gallotti

Executive Coach, Organizational Consultant, Collective Energy Catalyst

The future of coaching

The Group Coaching institute teaches business leaders, human resources professionals and coaches how to effectively problem-solve in the workplace. Whether in-person or remote, these skills can really elevate your employees' experience and business results. I created the Group Coaching Institute because I am convinced group coaching is the future of coaching: it’s more collaborative, more sustainable, and brings real change at the collective level.

Say hello

Meet Us

- Europe: +33 (0)6 80 90 43 16

- USA: +1 (917) 893 19 59

Our clients

Latest article

My books

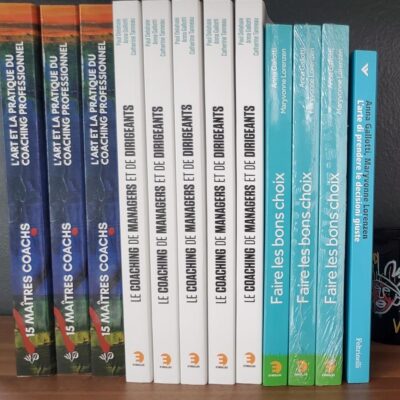

So far, I have written three books in collaboration with other authors:

“Make the right choices” – translated also in French and in Italian

“L’art et la pratique du coaching professionnel” – available in French

“Le coaching de managers et de dirigeants” – available in French